In this chapter we will analyze consumer choices. This is important to understand both

(i) the demand for goods and services that consumers consume as well as

(ii) supply of endowments the consumers (initially) possess (e.g. capital or labor). Our approach to understand consumer choices could be summarized in the following points:

1. observe real data about the pairs of consumption bundles chosen and prices of goods and services in that bundle,

2. construct preferences that represent the observed choices under observed prices,

3. represent constructed preferences by some utility function,

4. analyze theoretically (for the purpose of forecasting or past behavior explanation) the choices of consumers with derived utility function under various incomes and market prices. The following two sections will address all four points. At this level, however,

we start from the 2nd one rather than the 1st, i.e. we assume that the preferences of consumers are given and then conduct the analysis of points number 3 and 4. At the end we will go back to the 1st point.

Preferences

Consider a consumer faced with choices from a given set X. This is a set of all consumption bundles consumer may think to consume and is called a consumption set. At this level we will assume that X ⊂ R K + , where K stands for the number of goods. That is, we will consider consumption of nonnegative amounts of perfectly divisible goods, and assume that number of goods is finite.

One should note that K could be very large, though. Specifically, when differentiating goods economists use at least these four criteria:

• physical characteristics (clearly apple is different from orange, by its color, size, taste, flavor, etc.),

• location (clearly for a consumer located in Warsaw the goods delivered on Sahara desert give much less satisfaction, than on place),

• time (clearly the goods promised to be delivered the next quarter give lower satisfaction, than goods consumed today),

• state of the world (clearly an umbrella gives higher utility, when it is raining then not). One could perhaps think of some more criteria that differentiate goods, and the key insight, when doing so could be reasoned from so called law of one price: goods which prices differ, should be regarded in principal as distinct. That is, consumers need a good reason to purchase similar goods at different prices. All in all, one can easily see that in reality the number of goods can be infinite.

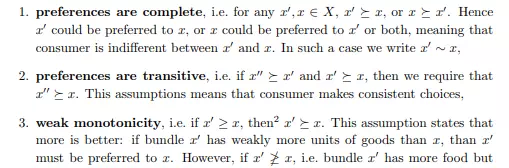

At this level we assume that K is finite1 , though, could be very large. The consumer is assumed to have preferences denoted by over bundles in X. If for x, x0 ∈ X we write x 0 x we mean that x 0 is weakly preferred to x. That is, consumer ranks his satisfaction from consuming x 0 weakly higher, than from consuming x, assuming both are available at no costs. Specifically, preferences describe consumer wants, but not what she wants from bundles she can afford. In what follows we need the following assumptions:

less clothing than x, then without additional information we cannot say which bundle is preferred. Weak monotonicity is sometimes strengthen to strong monotonicity, i.e. if x 0 ≥ x and x 0 6= x, then x 0 x meaning that, if x 0 has strictly more units of some good and weekly more of the others, then x 0 must be strictly preferred3 to x.