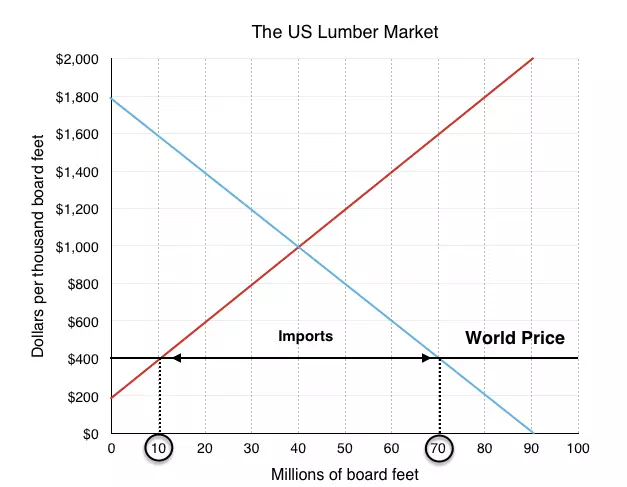

A tariff is defined as a tax on imported goods. The easiest way to show how it works is with an example. Below, we have continued the example from the beginning of this section: the US lumber market. In the domestic market, the domestic equilibrium price and quantity are $1,000/board feet, and 40 million board feet, respectively. This is denoted as PD = $1,000 and QD = 40 million. In this case, the world price, or PW is substantially lower than the domestic price. While this is not always the case, there is no incentive to import if PW is greater than PD (This model assumes that imports are identical to domestic products in every respect except for price).

With access to imports with prices as low as $400, American consumers will purchase significantly more lumber. Their quantity demanded will increase to 70 million units (40 million more than the domestic equilibrium). These consumers are significantly better off with the new access to cheap lumber.

Domestic producers, on the other hand, lose a large degree of surplus from the imports. Whereas before they supplied 40 million board feet of lumber at $1000, now they can only supply 10 million board feet. This is because many domestic firms are no longer able to compete with the foreign production and will either leave the market or decrease production.

With domestic production of 10 million and total production of 70 million, 60 million board feet of lumber are imported from Canada.

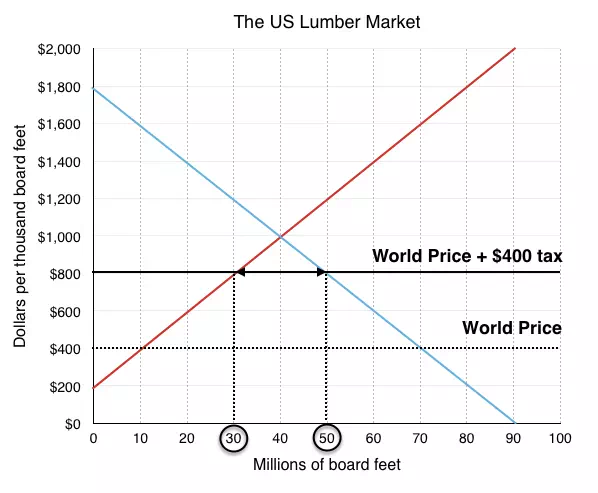

With such a significant portion of lumber production being imported, the government may choose to introduce a protectionist policy to restrict foreign competition, due to severe pressure from domestic producers. One important clarification about our model at this point is that the only surplus America cares about is domestic. Any producer surplus to Canadian firms is irrelevant in American decision making.

Suppose the government enacts a $400 tariff on imports to restrict competition. A tariff is a tax imposed on important goods or services. This creates an equilibrium price equal to $800 (world price + the $400 tariff). While this price is still below the domestic equilibrium, more domestic firms are now able to compete. In the new equilibrium, total quantity is 50 million board feet, 30 million of which are domestic. This means that imports have dropped from 60 million to 20 million board feet.

In this situation, domestic producers are better off, as they are now able to sell 20 million more units. Consumers, on the other hand, are worse off, as they face a higher price. The government is better off with revenue collected by the tariff. In Figure 4.10c, we have broken down the effects of the tariff on each of the market players.