The Global Crisis, along with ravaging the world economy, has awoken economists to the dangers of unchecked private debt. Excessive private leverage has been linked in recent papers to increased risks of financial crises (Schularick and Taylor 2012), weaker recoveries (Mian et al. 2013), and lower medium-term growth (Mian et al. 2017). A few papers in this burgeoning literature explore the fiscal costs of excess private leverage (Reinhart and Rogoff 2011) partly inspired by the staggering rise in advanced countries’ public debt in the aftermath of the recent crisis. However, the existing evidence and policy debate have so far revolved around financial crises and the associated costs of bank bailouts.

In a recent paper, we argue that excess private debt tends to spill over into the public-sector balance sheet regardless of whether the leverage cycle resulted in a crisis or a more orderly deleveraging process (Mbaye et al. 2018a). Our results suggest that the spillover operates mainly through growth – and not as much through the explicit assumption of liabilities by the government. The basic mechanism works as follows – whenever the private sector is caught in a debt overhang, the ensuing deleveraging process weighs on activity, thus prompting the government’s response through higher borrowing to support the economy. We show that this is a recurrent pattern through history, where excess private debt systematically leads to higher public debt.

New debt data for 190 countries

The analysis exploits new historical private and public debt data available in the Global Debt Database (Mbaye et al. 2018b), a unique dataset that provides an unparalleled account of private, public, and total debt for 190 countries going as far back as 1950. This allows us to study the dynamics of private deleveraging beyond the realm of a few major advanced and emerging markets economies, as is typical of most existing studies.

Anatomy of private deleveraging

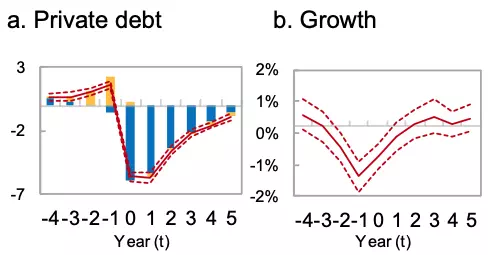

We define a private deleveraging spell as the distance from a peak to the ensuing trough in the private debt-to-GDP ratio, identifying 535 private deleveraging episodes spread across several decades and various income levels. Figure 1 tracks the macroeconomic dynamics around the start of private deleveraging spells, indexed as year t = 0. It plots the results of event-studies à la Gourinchas and Obstfeld (2012), where each bar/line denote the change in the macroeconomic aggregate in question relative to ‘normal times’. To get a firmer grasp of private debt dynamics, we break down changes in the private debt-to-GDP ratio into the impact of the interest rate-growth differential – which we refer to as ‘macro-related changes’ – and the remaining component – which we call ‘leverage flows’.

As expected, the private debt ratio grows faster in the run up to the deleveraging episode and contracts afterwards. However, a closer look at the underlying dynamics shows a less predictable picture – while the debt ratio is rising at an increasingly faster pace before the deleveraging episode, leverage flows (blue bars) are growing at an increasingly slower pace, turning negative one year before deleveraging begins. This suggests that the process of debt repayment starts earlier than visible in the private debt ratio.

Figure 1 Macroeconomic dynamics during private deleveraging

Early deleveraging efforts are not visible in the debt ratio because of the dynamics of the ‘macro-related changes’ (Figure 1, panel a, yellow bar), especially GDP growth (panel b). The adverse impact on GDP more than offsets the deleveraging efforts of the private sector, thus contributing to pushing the debt ratio up. But the recession is short-lived, with growth returning to normal a year after the start of the deleveraging episode.

Public debt, on the other hand, tends to increase faster than normal during private deleveraging episodes (Figure 1, panel c). The surge in public debt is front-loaded, starting one year before the beginning of the deleveraging episode, before subsequently tapering off as growth bounces back and the deleveraging process takes root.

Finally, total debt goes up in the run up to the deleveraging episode, before stabilising early in the deleveraging process, and eventually declining (Figure 1, panel d). The story of the typical private deleveraging episode is a success story in that, although private debt is partially ‘replaced’ with public debt, in the end, the total stock of debt in the economy declines and activity bounces back. However, this is not always the case. Our paper documents a special type of deleveraging episodes (called ‘growthless’) where total debt is higher at the end of the deleveraging spell. This less-successful story of private deleveraging is hardly an exception. It fits about a quarter of deleveraging episodes in our sample.

Spillovers from the private to the public sector

To ascertain whether (at least part of) these historical regularities are indeed due to spillovers from excess private borrowing into public debt, one needs to establish that there is causality running from private deleveraging to public debt and growth.

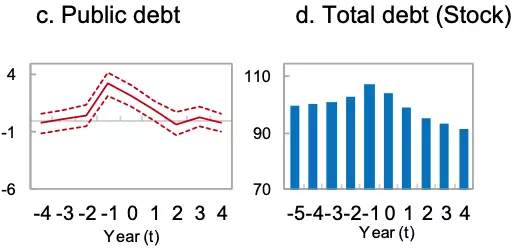

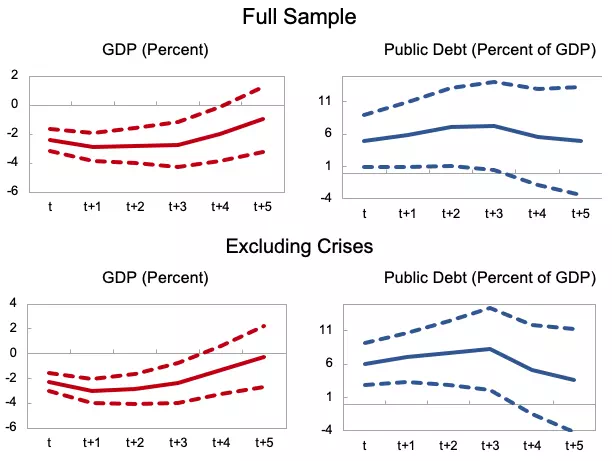

Figure 2 plots our estimate of the causal impact of private deleveraging on growth and public debt, based on an Inverse Propensity Weighting Regression Adjustment (IPWRA) framework. It shows the cumulative impact of private deleveraging started in t, affecting GDP and public debt over a five-year horizon. The results give overwhelming support to our hypothesis. Private deleveraging seems to cause both a slowdown in growth and a rise in public debt. On average, the onset of a private deleveraging spell induces a 7.2% of GDP rise in public debt over the following 3 years.

It is not just a crisis story

Strikingly, excluding financial crisis episodes from the analysis yields similar results (Figure 2 bottom panel). That is, even in the absence of a crisis, private deleveraging causes a growth slowdown and a rise in public debt.

Figure 2 Cumulative impact of private deleveraging on GDP and public debt

Conclusion

These findings invite many interpretations and even more questions. One (rather provocative) interpretation is that we are all implicitly guaranteeing our neighbours’ mortgages and corporate liabilities. In other words, governments act as ‘debtors of last resort’ by issuing new debt on behalf of all taxpayers to support activity through the deleveraging process. Regardless of one’s take on whether this is a good or a bad thing, many would agree that these spillovers call for integrating both public and private liability risks in our approach to debt sustainability.