Many of the recent successes of machine learning and artificial intelligence have been driven by the rapid development of techniques to make accurate predictions from vast amounts of data. Typically, in such ‘supervised learning’ problems, an algorithm is trained to take a vector of features (for example, the pixels of a medical scan) and use this to produce a classification (for example, whether or not the scan reveals the presence of a tumour). Other prominent commercial examples are targeted online advertisements that use past consumer behaviour to predict future purchase decisions, and underwriting in credit markets, where features like the applicant’s income and credit history are used to predict the likelihood of default. Agarwal et al. (2018) provide a good survey of these and similar applications.

Decisions informed by algorithmic predictions can have both positive and negative effects on the welfare of individual consumers. Credit markets are a prime example – consider a hypothetical consumer who, before the introduction of a machine-learning credit screening algorithm, would have been offered a mortgage deal with a 5% interest rate. If the bank begins using a prediction algorithm that changes the classification of the consumer from highly creditworthy to less creditworthy, the consumer could be excluded from the mortgage market altogether or be offered a higher interest rate. Conversely, consumers that were previously excluded from the mortgage market might be offered mortgages if algorithms learn that their ‘true’ credit risks are lower than previously thought.

This simple example highlights a deeper issue related to the widespread adoption of machine learning techniques, namely, that such adoption can have important distributional consequences. Increasingly, discussions of the impacts of artificial intelligence are concerned with the question of whether the rapid growth in technology will foster or perpetuate inequality (e.g. O’Neill 2016).1 In the case of credit screening, if new algorithms consistently price out members of disadvantaged racial groups, then policymakers might well view any predictive efficiency gains they create in a more critical light.

In a recent paper (Fuster et al. 2018), we study the effect of machine learning on credit markets. We build simple theoretical frameworks to better understand the issues involved, and empirically estimate the likely impacts using a large administrative dataset from the US mortgage market, comprising about 10 million mortgage loans made between 2009 and 2013. In this setting, we compare the predictions that a hypothetical lender would make when using traditional statistics (e.g. standard Logit models) to those when using supervised machine learning techniques such as the Random Forest and XGBoost.

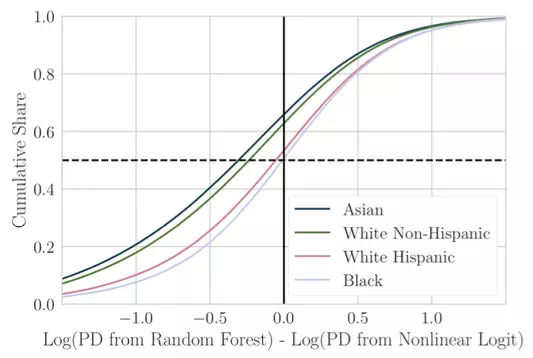

Figure 1, taken from our paper, shows our first key result. On the horizontal axis is the change in the log predicted default probability as lenders move from traditional predictive technology (a “Logit” classifier) to machine learning technology (a “Random Forest” classifier). On the vertical axis is the cumulative share of borrowers from each racial group that experience a given level of change.

Figure 1 Winners and losers of machine-learned credit allocation

Borrowers to the left of the solid vertical line represent ‘winners’ who are classed as less risky by the more sophisticated algorithm than by the traditional model. Reading off the cumulative share around this line, we see that about 65% of White Non-Hispanic and Asian borrowers win, compared with about 50% of Black and Hispanic borrowers. To summarise, we find that the gains from new technology are skewed in favour of racial groups that already enjoy an advantage, while disadvantaged groups are less likely to benefit in this dataset.

It is important to note that this result does not arise from any unlawful discrimination. In our setup and evaluation, all algorithms comply strictly with the letter of current US law. In particular, none of these predictions takes as inputs sensitive variables such as the race of borrowers. Rather, the unequal effects of new technology arise from the use of highly nonlinear combinations of variables such as borrowers’ income, credit scores, and loan-to-value ratios.

What then drives these unequal effects across racial groups? One reason could be that the highly nonlinear combinations of permissible variables (such as income, credit scores, and LTV ratios) employed by the machine learning algorithms essentially proxy for, or triangulate, borrowers’ race. This would allow the algorithms to capture the association between race and predicted default but in a way that sidesteps regulation – without directly including race in the model. A different reason could be that, due to historic injustice or otherwise, certain racial groups tend to have combinations of permissible variables (such as income or wealth) that are genuinely predictive of default in a manner that is independent of race. An algorithm that can identify these combinations of permissible variables would hurt the minority group due to its flexibility, not due to triangulation. Disentangling these different sources of inequality seems key for effective policy formulation.

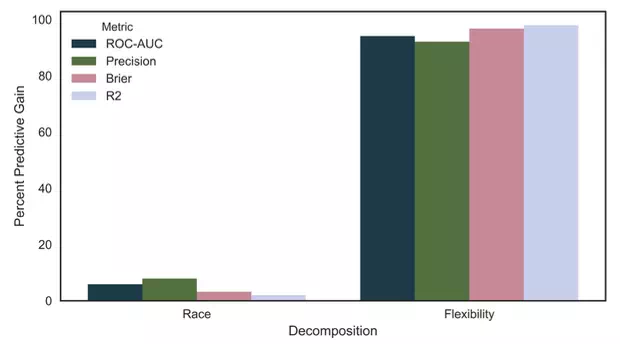

Figure 2 Causes of inequality in machine-learned credit allocation

Figure 2 shows a decomposition that examines whether the unequal effects that we detect are driven by triangulation, or by the flexibility of the new technology. To arrive at these numbers, we follow a two-step thought experiment. In the first step, we begin with a Logit model that only contains the permissible variables, and then augment this simple model to ‘see’ race as an explanatory variable. In the second step, we estimate the Logit model explicitly including the race of the borrower, and then augment its flexibility, by changing the estimation technology from the simple Logit to the more sophisticated Random Forest.

Clearly, both steps ought to improve predictive accuracy. The three left bars in Figure 2 show the percentage of the total predictive improvement – according to three different commonly employed out-of-sample performance metrics – that is achieved in the first step (i.e., augmenting the simple model by adding borrower race). If the effects of new technology were chiefly driven by triangulation, then the lion’s share of performance improvements would come from this step, i.e. this number would be close to 100%. Instead, we find it to be below 10%, suggesting that triangulation is not greatly important, while improved flexibility is primarily responsible for the effects seen in Figure 1. (The order of decomposition is clearly important in this exercise but does not affect our qualitative results.)

We go further, using the predicted default probabilities to assess how lenders using old and new technologies would treat different borrowers in equilibrium. We find that the unequal effects in Figure 1 are strongly reflected in lenders’ decisions at the intensive margin, that is to say, they affect the interest rates offered to borrowers that are granted mortgages. However, at the extensive margin – i.e. when deciding whether borrowers are granted mortgages at all – machine learning benefits disadvantaged groups.