analyses of economic wellbeing rely almost exclusively on wage or income data. Though measures of income are readily available from many data sources, recent studies have emphasised that consumption is a better measure of wellbeing than income, and a growing number of studies have examined trends in economic wellbeing using consumption (Cutler and Katz 1991, Slesnick 2001, Krueger and Perri 2006, Attanasio et al. 2007, Fisher et al. 2015, Aguiar and Bils 2015, Meyer and Sullivan 2003, 2008, 2011, 2017).

Economic wellbeing, however, depends on the consumption of not just goods and services, but also the consumption of time. Understanding the joint distribution of consumption and leisure is particularly important when analysing trends in wellbeing over time given major policy initiatives that are explicitly designed, in part, to reduce leisure time, such as welfare reform (Moffitt 2006) or, more recently, efforts to expand work requirements for other federal programs such as SNAP and Medicaid.

In order to construct a more comprehensive measure of economic wellbeing, we combine consumption and time use data by imputing with a high degree of accuracy the amount of leisure families consume in the Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE). Specifically, we first estimate the relationship in the time use data between leisure and other observable characteristics that are also available in the CE, such as age, gender, marital status, and the amount of hours spent working in a typical week. We then use these estimates to predict leisure for each family in the CE based on these observable characteristics.

An important aspect of estimating the leisure distribution is that time-use diaries capture leisure time for a single day, while we would like to have an accurate prediction of leisure over a long period, such as a quarter, that aligns with our reference period for our consumption measures. Thus, we use data on daily leisure to predict leisure over a longer period. Specifically, we model leisure as having permanent and transitory components, where the permanent component is average leisure over a long period while the transitory component reflects day-to-day variation around this long-run average. We find that with the characteristics we observe in the time use data, in particular time spent working in a week, our prediction equations can capture the vast majority of the long-term differences in leisure across individuals.

Using this approach, we predict leisure for all adults in the CE for years when information from time use surveys is available between 1972 and 2016. Having a measure of leisure for all adults in the CE has the added advantage that we can aggregate leisure up to the family level. Time use surveys typically only provide leisure time information for a single individual in the family. Thus, past work on time use has examined individuals, even though more than 80% of people live in families. Individuals in families typically share resources including time, but often do not consume the same amount of leisure. It is often optimal to specialise instead of to share equally, and complicated forms of compensation can and do occur within the family. In such a situation, looking at inequality in individual leisure provides an inaccurate view of the distribution of wellbeing.

For the results presented here, our definition of leisure includes activities where time and expenditures are complements, such as ‘entertainment/social activities/relaxing’ and ‘active recreation’, as well as time spent sleeping, eating, and on personal care that can be thought of as intermediate inputs but also provide direct utility. Finally, we include some activities that may be categorised as both leisure and home production, such as gardening. As we report in Han et al. (2018), survey respondents tend to rank these categories of time use high based on how enjoyable they are or how much happiness or meaning they yield.

Our measure of consumption is constructed to address concerns that at least some components of consumption are under-reported in surveys. Specifically, we focus on those components of consumption that are well-measured, including food at home, rent plus utilities, gasoline and motor oil, the rental value of owner-occupied housing, and the rental value of owned vehicles. Recent research has shown that these components of consumption from the CE compare quite favourably to national accounts, both in levels and in changes over time (Bee et al. 2015). In order to draw conclusions about changes in consumption inequality from evidence on the well-measured components, it is critical that these components are equally important for high- and low-consumption households. It is also important that price changes for well-measured consumption mirror the changes for overall spending. Meyer and Sullivan (2017) show that both these conditions hold: well-measured consumption is roughly a constant share of overall consumption throughout the distribution, and the price of the bundle of well-measured goods has not changed noticeably relative to the prices for all goods.

Consumption and leisure trends

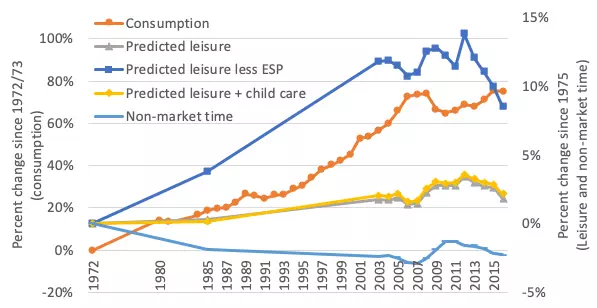

Over the past four decades, average real family consumption has risen significantly, while family leisure time has been relatively flat. As we show in Figure 1, consumption rose by 75% between 1972 and 2016, while family leisure grew by less than 2%. Much of the rise in consumption occurred prior to 2003. Consumption fell sharply during the Great Recession and then bounced back a bit, but average real consumption in 2016 was less than 1% higher than it was at its previous peak in 2008. For leisure, much of the rise occurred between 1985 and 2012. The pattern is quite similar when childcare is added to leisure, but we see a more noticeable rise in leisure over time when eating, sleeping, and personal care are excluded. Between 1972 and 2016, this narrower definition of leisure rose by 8.5%. Unlike leisure, non-market time, which includes both leisure and home production, declined over the past four decades, except for a brief period around the Great Recession when it rose.

Figure 1 Changes in mean family level consumption and predicted leisure, CE, 1972-2016

Notes: ESP: eating, sleeping, and personal care. Changes in consumption are adjusted for inflation using the biased corrected CPI‐U‐RS. Family-level leisure and non‐market time are per adult and consumption is adjusted for family size using the NAS‐recommended equivalent scale.

Trends in inequality in consumption and leisure

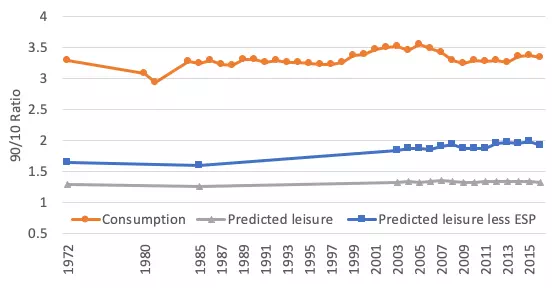

Leisure is much less dispersed than consumption, as is shown in Figure 2, which reports the ratio of the 90th percentile to the 10th percentile (the 90/10 ratio) for consumption, leisure, and leisure, excluding time spent eating, sleeping, and in personal care. A family at the 90th percentile of the consumption distribution in 2016 consumes 3.4 times that of a family at the 10th percentile. In the case of leisure, a family at the 90th percentile consumes only about 1.3 times the leisure of a family at the 10th percentile. While dispersion is larger for narrower definitions of leisure, even when time spent eating, sleeping, and in personal care are excluded from leisure, the 90/10 ratio (1.93 in 2016) is much lower than that for consumption.

Figure 2 Inequality in family level consumption and predicted leisure, CE, 1972-2016

Note: See notes to Figure 1 for more details.

Over the past four decades we have seen only a modest increase in both leisure and consumption inequality. Between 1972 and 2016, the 90/10 ratio for consumption rose by about 1.5% and the 90/10 ratio for leisure grew by about 2%. We see a more noticeable rise in inequality for narrower measures of leisure: the 90/10 ratio for leisure excluding eating, sleeping, and personal care rose by 17% between 1972 and 2016.

Bivariate analyses of consumption and leisure

The key advantage of having measures of both leisure and consumption in the same data source is that it enables us to examine changes in these important components of wellbeing for the same families. At a point in time, it is not clear if the amount of leisure is greatest for families with low consumption (in which case inequality of consumption would overstate the dispersion of economic wellbeing) or families with high consumption (in which case inequality of consumption would understate overall dispersion in economic wellbeing). Similarly, the change in the overall dispersion in economic wellbeing depends on whether the growth in leisure over time has been greater for families with low consumption or families with high consumption.

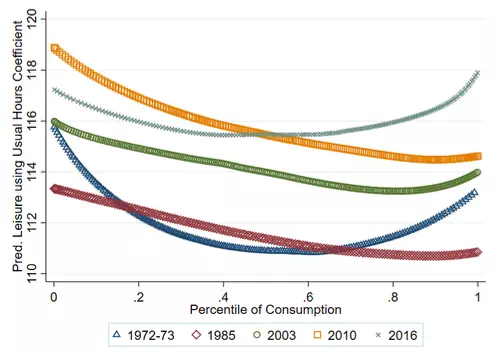

The bivariate relationship between mean leisure and the percentile of the consumption distribution (Figure 3) shows that leisure typically declines with consumption, but the differences are small. For example, in 2016, leisure time at the 10th percentile of consumption is only about 1% greater that leisure time at the 50th percentile of consumption, and leisure time at the 90th percentile is similar to that at the 10th. The negative relationship between leisure and consumption is greatest in 2010, a time when annual unemployment had reached its peak. In results not shown here, we also find that the leisure-consumption gradient is largest for single parent families and for single individuals, and smallest for families with a head age 65 and over. Between 1985 and 2003, the period that surrounds welfare reform, the bivariate relationship weakened only for single parent families. This pattern is consistent with welfare reform’s emphasis on market work by those with the fewest resources.

Figure 3 Bivariate distribution of consumption and leisure

Notes: Predicted Leisure is smoothed using LOWESS (locally weighted scatterplot smoothing) regression of predicted leisure on consumption percentiles. Family level leisure is per adult and consumption is adjusted for family size using the NAS‐recommended equivalent scale.

Implications

Our findings contribute to a growing national debate in the US on trends in the distribution of economic wellbeing. Looking at leisure and consumption together for the same families, we find a negative relationship between consumption and leisure, but the relationship is fairly weak. Therefore, accounting for both leisure and consumption, as opposed to just consumption, when measuring economic wellbeing implies somewhat less inequality. Moreover, patterns in the relationship between leisure and consumption suggest that both social welfare policies and the business cycle can alter the economic wellbeing of families, not only by altering resources consumed, but also through their effect on leisure.