An enduring goal of health policy around the world is improving quality while reducing costs. This goal is particularly pressing in the US, where both healthcare spending levels and growth have exceeded other developed countries for many years.

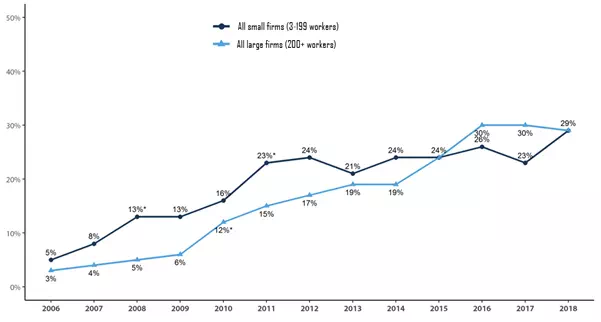

Payers and policymakers have devised various approaches to encourage the utilisation of high-value services and discourage wasteful and unnecessary care. These approaches can generally be categorised into those that operate on the supply-side of the health economy, such as pay-for-performance schemes, and those that influence the demand side. Classic demand-side mechanisms include patient cost-sharing in the form of deductibles, coinsurance and co-payments, which mitigate the phenomenon of moral hazard (Pauly 1968). However, with healthcare costs rising at an unsustainable pace, payers in the US have turned towards higher-powered demand-side incentives, including high-deductible health plans.1 Approximately half of Americans receive insurance through their employers, and the percentage of workers enrolled in high-deductible health plans has increased from under 5% to almost a third since 2006 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Percentage of covered workers enrolled in a high-deductible health plan, 2006-2018

Source: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation 2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey

While high deductibles are most common in the US, general medical and pharmacy deductibles are used in other developed countries, such as the Netherlands and Switzerland (Paris et al. 2016). Given the spread of high-deductible health plans, also referred to as ‘consumer-directed’ health plans, much research has sought to understand whether they are achieving their intended goals.

What does the theory say?

As early as the 1960s, Arrow showed that optimal coverage from an individual’s point of view is full insurance above a deductible, given risk-averse consumers and actuarially fair insurance (Arrow 1963, 1973). The standard theory of moral hazard predicts that raising deductibles will lead to lower spending levels, as deductibles raise the average prices faced by consumers. Later work has discussed the implications of incorrect beliefs about the value of care driving patient demand (Pauly and Blavin 1998). Depending on the direction of such biases, spending reductions following exposure to higher out-of-pocket costs may or may not be efficient or welfare-improving.

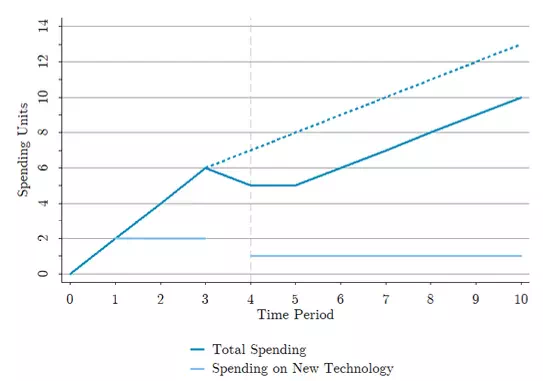

In addition to depressing spending levels, high deductibles hold the potential to reduce spending growth. The latter outcome will depend on whether deductibles affect what drives spending growth, commonly thought to be the adoption and diffusion of new and costly but potentially beneficial technologies (Weisbrod 1991, Chandra and Skinner 2012). Figure 2 shows how a total spending trajectory may respond to a hypothetical introduction of a high deductible in an arbitrary fourth period. The darker solid line is consistent with the high deductible reducing spending on both old and new technology, while the darker dashed line is what we would expect if the change only affected the use of new technology. In both cases, cost growth is lower, as evidenced by a flatter slope than the pre-period.2

Figure 2 Spending growth following a coverage change

What do the data show?

Credible identification of the effects of high deductibles is challenging, given that healthier individuals are more likely to select into less generous plans. As a result, much empirical work to date has exploited natural experiments where a population faces an exogenous change in their health insurance benefits or benefit offers. Haviland et al. (2016) use differences-in-differences estimation to quantify the effects of firm choices to offer high-deductible health plans on spending growth. They find that firms offering high-deductible health plans experience significantly lower cost growth relative to firms only offering lower deductible plans for each of the three years in their post-period. Brot-Goldberg et al. (2017) study employees of a single firm that mandated a switch from a generous zero-deductible plan to a high-deductible plan, with individual and family deductibles in excess of $1000 and $3000, respectively. They find that the switch caused a spending reduction of approximately 12% of firm-wide spending. In decomposing this effect, they find that employees reduced quantities of care said to be of high and low average value, consistent with biased beliefs and greater sensitivity to spot prices over true shadow prices.

What about the effects of high-deductible health plans on long-term spending growth, use of high- and low-value new technology, and health outcomes? Until recently, the effect of cost-sharing on long-term spending growth had only been explored with national time series data. Peden and Freeland (1998) find that over half of the growth in US national health expenditures from 1960 to 1993 was due to increasing levels of insurance coverage, defined as the share of spending paid for by third parties. While their results are striking, their analysis is limited by the use of nationally aggregated data, and their time period precedes the advent of high-deductible health plans.

In recent work, we seek to estimate the relationship between high deductibles, specifically, and the growth in total healthcare spending on all medical goods and services (Frean and Pauly 2018). We leverage cross-sectional variation across US states in the proportion of privately insured individuals covered by plans with high deductibles and relate that variation to multiple categories of healthcare spending across states. Over our data period of 2002–2016, spending growth in the US exceeded 40% in real terms. We define a state’s average deductible among privately insured employees as the product of the proportion of employees with a non-zero deductible and the conditional average deductible among such employees. This measure more than triples in magnitude over our data period, from approximately $450 in 2002 to almost $1,900 in 2016.

Across a range of empirical specifications, we find a significant negative relationship between average deductible levels and current-period growth in both total and private spending. While this result is extremely robust, we do not find a significant relationship between the change in the average deductible since the previous period and either measure of spending growth. A significant relationship between private deductibles and total spending—which includes spending by public insurance programs and spending on behalf of the uninsured—is indicative of spillover effects, which we confirm in models of exclusively public spending growth. We also find a stronger negative relationship between average deductibles and pharmaceutical spending growth (relative to models of total spending or hospital spending), which is consistent with large volumes of new technologies and potentially greater consumer discretion in the sector.

Our results strongly confirm and mirror those found by Peden and Freeland (1998) and underscore the need for ongoing research on how high-deductible plans are affecting long-term spending patterns. The magnitude of our estimates suggests that annual growth in total spending per capita from 2002–2014 would have been about one percentage point higher had average deductibles remained at their 2002 levels. Given this considerable effect on spending growth, the natural next step is to explore whether or how that impact affects health outcomes. More detailed data, such as insurance claims, in combination with innovative identification strategies, will allow for estimation of the effects of high deductibles on actual measures of diffusion of different technologies. Importantly, heterogeneity in these effects across technologies with varied incremental clinical value will speak to the welfare implications of the US insurance market’s shift towards high deductible plans.