In most histories of how Americans became so polarized, the Great Inflation of the 1970s is given short shrift — sometimes no shrift at all. This is wrong. Inflation was as pivotal a factor in our national crackup as Vietnam and Watergate.

Inflation changed how Americans thought about their economic relationships to their fellow citizens — which is to say, inflation and its associated economic traumas changed who we were as a people. It also called into question the economic assumptions that had guided the country since World War II, opening the door for new assumptions that have governed us ever since. Here is the story:

The United States of the 1960s experienced many social upheavals. But in one realm, all was copacetic. The economy roared. The gross domestic product was increasing between 2 percent and 6 percent, wages grew, jobs were stable. The year 1968 was an annus horribilis — assassinations, riots, a bitter presidential race. But the Economic Report of the President for that year reflected at length on — imagine this — “the problem of prosperity.”

Slowly, though, inflation entered the picture. It hit 5.7 percent in 1970, then 11 percent in 1974. Such sustained inflation was something that had never happened in stable postwar America. And it was punishing. For a family of modest means, a trip to the supermarket was now a walk over hot coals.

How different this was from previous economic crises! The Great Depression, the 20th century’s first economic emergency, made most Americans feel a degree of neighborly solidarity. The government wasn’t measuring median household income in the 1930s, but a 2006 Department of Labor study pegged the average household income of 1934-36 at $1,524. Adjust for inflation to 2018, that’s about $28,000, while the official poverty level for a family of four was $25,100. In other words, the average family of 1936 was near poor. Everyone was in it together, and if Bill couldn’t find work, his neighbor would give him a head of cabbage, a slab of pork belly.

But the Great Inflation, as the author Joe Nocera has noted, made most people feel they had to look out for themselves. Americans had spent decades just getting more and more ahead. Now, suddenly, they were falling behind.

Throw in wage stagnation, which began in the early ’70s, and deindustrialization of the great cities of the North. Pennsylvania’s Homestead Works, which had employed 20,000 men during the war, started shrinking, closing forever in 1986. Today that tract of land along the Monongahela River where the works once stood is home to the usual chain restaurants and big-box stores, those ubiquitous playpens of the low-wage economy.

Inflation also produced the manic search for “yield” — it was no longer enough to save money; your money had to make money, turning every wage earner into a player in market rapaciousness. The money market account was born in the 1970s. Personal investing took off (remember “When E.F. Hutton talks, people listen”?).

Even as Americans scrambled for return, they also sought to spend. Credit cards, which had barely existed in 1970, began to proliferate. The Supreme Court’s 1978 decision in Marquette National Bank of Minneapolis v. First of Omaha Service Corporation opened the floodgates for banks to issue credit cards with high interest rates. Total credit card balances began to explode.

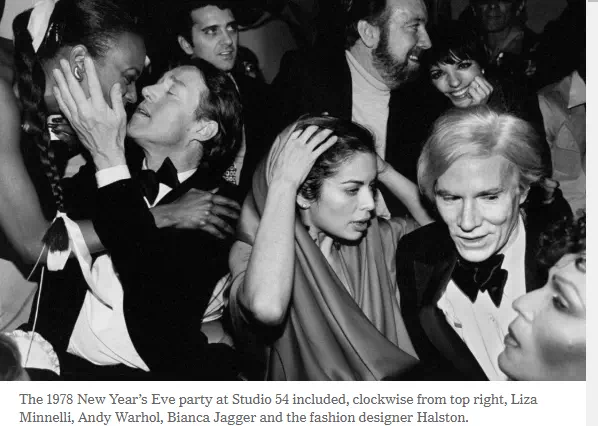

Then along came Ronald Reagan. The great secret to his success was not his uncomplicated optimism or his instinct for seizing a moment. It was that he freed people of the responsibility of introspection, released them from the guilt in which liberalism seemed to want to make them wallow. And so came the 1980s, when the culture started to celebrate wealth and acquisition as never before. A television series called “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” debuted in 1984.

So that was the first change flowing from the Great Inflation: Americans became a more acquisitive — bluntly, a more selfish — people. The second change was far more profound.

For decades after World War II, the economic assumptions that undergirded policymaking were basically those of John Maynard Keynes. His “demand side” theories — increase demand via public investment, even if it meant running a short-term deficit — guided the New Deal, the financing of the war and pretty much all policy thinking thereafter. And not just among Democrats: Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon were Keynesians.

There had been a group of economists, mostly at the University of Chicago and led by Milton Friedman, who dissented from Keynes. They argued against government intervention and for lower taxes and less regulation. As Keynesian principles promoted demand side, their theories promoted the opposite: supply side.

They’d never won much of an audience, as long as things were working. But now things weren’t, in a big way. Inflation was Keynesianism’s Achilles’ heel, and the supply-siders aimed their arrow right at it. Reagan cut taxes significantly. Inflation ended (which was really the work of Paul Volcker, the chairman of the Federal Reserve). The economy boomed. Economic debate changed; even the way economics was taught changed.

And this, more or less, is where we’ve been ever since. Yes, we’ve had two Democratic presidents in that time, both of whom defied supply-side principles at key junctures. But walk down a street and ask 20 people a few questions about economic policy — I bet most will say that taxes must be kept low, even on rich people, and that we should let the market, not the government, decide on investments. Point to the hospital up the street and tell them that it wouldn’t even be there without the millions in federal dollars of various kinds it takes in every year, and they’ll mumble and shrug.

There are signs this mind-set is changing. The Trump tax cut of 2017 is consistently unpopular. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Democrat of New York, speaks of a top marginal tax rate of 70 percent on income over $10 million, and instead of getting laughed out of town, she prompts a serious public debate.

Still, we have a long way to go. Dislodging 40-year-old assumptions is a huge job. The Democrats, for starters, have to develop and defend a plausible alternative theory of growth.

But others have a responsibility here too — notably, our captains of commerce. They have enormous power, and in a country this polarized, they can move moderate and maybe even conservative public opinion in a way that Democratic politicians, civic leaders and celebrities cannot.

They will always be rich. But they have to decide what kind of country they want to be rich in. A place of more and more tax cuts for them, where states keep slashing their higher-education spending and tuitions keep skyrocketing; where the best job opportunity in vast stretches of America is selling opioids; where many young people no longer believe in capitalism and record numbers of them would leave this country if they could? Or a country more like the one they and their parents grew up in, where we invested in ourselves and where work produced a fair and livable wage?