I’ve been coming around to the belief that most modern arguments over “socialism” are a waste of time, because the content of the term has become so nebulous. When you drill down a bit, a lot of “socialists” are really just saying that they would like to have government play a more active role in providing various benefits to workers and the poor, along with additional environmental protection.

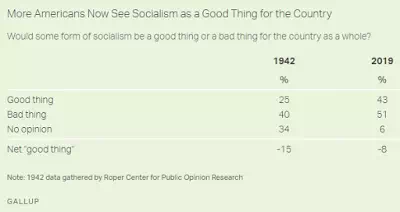

Here is some evidence on how Americans perceive “socialism” from a couple of Gallup polls, one published in May 2019 and one in October 2018. The May 2019 survey found that compared to 70 years ago, not long after World War II, both more American favor and oppose socialism–it’s the undecideds that have declined.

But when people say they are in favor of “socialism” or opposed to it, what do they mean? The same survey found that when asked a question about market vs. government, there were heavy majorities in favor of the free market being primarily responsible for technological innovation, distribution of weal, and the economy overall, and modest majorities in favor of the free market taking the lead in higher education and healthcare. Government leadership was preferred in taking the lead in online privacy and environmental protection.

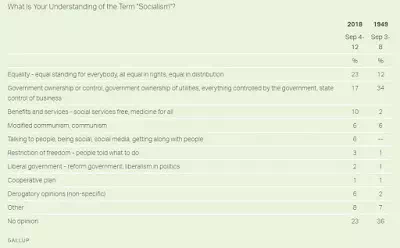

There are apparently a reasonable number of those who think socialism is a good thing, but would prefer to see free markets be primarily responsible in many areas. Clearly, this form of socialism isn’t about government control of the means of production. The October 2018 Gallup survey asked more directly what people primarily meant by socialism, and compared the answer to a poll from the aftermath of World War II.

Seventy years ago, the most common answer for a person’s understanding of the term “socialism” was government economic control, but that answer has fallen from 34% to 17% over time. Now, the most common answer for one’s understanding of socialism is that it’s about “Equality – equal standing for everybody, all equal in rights, equal in distribution.” As the Gallup folks point out, this is a broad broad category: “The broad group of responses defining socialism as dealing with `equality’ are quite varied — ranging from views that socialism means controls on incomes and wealth, to a more general conception of equality of opportunity, or equal status as citizens.” The share of those who define “socialism” as “Benefits and services – social services free, medicine for all” has also risen substantially. There are also 6% who think that “socialism” is “Talking to people, being social, social media, getting along with people.”

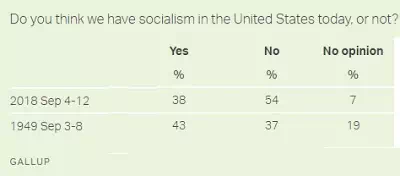

The October 2018 survey also asked whether the US already had socialism. Just after World War II, when the US economy had experienced extreme government control over the economy and most people defined “socialism” in those terms, 43% said that the US already had socialism. Now, the share of those who believe we already have socialism has dropped to 38%. One suspects that most of those who think we have socialism are not happy about it, and a substantial share of those who think we don’t have socialism wish it was otherwise. Clearly, they are operating from rather different visions of what is meant by “socialism.”

There’s no denying that the word “socialism” adds a little extra kick to many conversations. Among the self-professed admirers, “socialism” is sometime pronounced with an air of defiance, as if the speaker was imagining Eugene Debs, five times the Socialist Party candidate for President, voting for himself from a jail cell in the 1920 election. In other cases, “socialism” is pronounced with an air of smiling devotion in the face of expected doubters, reminiscent of the very nice Jehovah’s Witnesses or Mormons who occasionally knock on my door. In still other cases, “socialism” is pronounced like a middle-schooler saying a naughty word, wondering or hoping that poking round with the term will push someone’s buttons, so we can mock them for being uncool. And “socialism” is sometime tossed out with a world-weary tone, in a spirit of I-know-the-problems-but-what-can-I-say.

My own sense is that the terminology of “socialism” has become muddled enough that it’s not useful in most arguments. For example, say that we’re talking about steps to improve the environment, or to increase government spending to help workers. One could, of course, could have an argument over whether the countries that have bragged most loudly about being “socialist” had a good record in protecting worker rights or the poor or the environment. One side could yelp about Sweden and the flaws that arise in a market-centric economy; the other side could squawk about the Soviet Union or Venezuela and the flaws of a government-centric economy.

While those conversations wander along well-trodden paths, they don’t have much to say about–for example–how or if the earned income tax credit should be expanded, or the government should assist with job search, or if the minimum wage should rise in certain areas, or how a carbon tax would affect emissions, or how to increase productivity growth, or how to address the long-run fiscal problems of Social Security. Bringing emotion-laden and ill-defined terms like “socialism” into these kinds of specific policy conversations just derails them.

Thus, my modest proposal is that unless someone wants to advocate government ownership of the means of production, it’s more productive to drop “socialism” from the conversation. Instead, talk about the specific issue and the mixture of market and government actions rules that might address it, based on whatever evidence is available on costs and benefits.