There are different ways of modeling the informal sector adopting a non-Marshallian view of labour markets.19 Starting from the classical Harris-Todaro framework, early modeling in this area has been very prolific.

The basic analytical set up used by this literature is similar to that used in the literature on migration (Todaro (1969) and Harris and Todaro (1970)) and the modeling approach adopted by the migration with search literature. As pointed out by Zenou (2008), the earlier analytical framework—where only one side (i.e., the worker) is modeled (Fields (1975))—differs from later set ups that have incorporated the Mortensen-Pissarides model in a migration equilibrium.

The early studies by Todaro (1969) and Harris and Todaro (1970) capture informality by building a model of two geographically distinct markets that are segmented and in which two different wage equilibria prevail (wage duality), where wages in the formal sector can turn out to be higher-than-market-clearing wages.20Brueckner and Zenou (1999b) add a land market to the standard Harris-Todaro framework where wages are exogenously fixed. The idea of identifying the informal labour market with the disadvantaged sector of a market segmented by rigidities in the formal sector dates back to Lewis (1954) and the idea of infinite labour supply.

More recent work, like Brueckner and Zenou (1999a), take a different approach and introduces efficiency wages. Developments in the theory of imperfect information allow to introduce labour dualism as a result of a firm’s response to adverse selection and moral hazard problems. In general, there are many models that can be used to justify duality and the presence of a higher wage in the formal sector, but this always requires an ad hoc assumption about some features characterizing the formal rather than the informal sector.

Yet another initial way to model informality involves cost-benefit analysis. Within this approach, the informal sector is seen as an unregulated, largely voluntary, sector (Lucas (1978) and Rauch (1991)), where agents ponder the costs of becoming formal against the benefits of being informal. In chapter IV we will review recent advances in modeling informality in the presence of labour frictions, namely the search-matching theoretical framework and its multi-sectoral extensions. Relative to the models of the Harris-Todaro tradition, the richer labour market structure of the search-matching framework determines the wage in the formal sector endogenously, and allows for a wider range of effects to be analyzed. Relative to the voluntary view of informality, the search-matching approach microfounds the decision of firms and workers to enter the formal/informal sector, while distinguishing among the three margins of informality by focusing on the flows between formal and informal labour market, and unemployment.

INFORMALITY AND LABOUR MARKET FRICTIONS

Building on the earlier literature, a variety of more sophisticated models has been developed to portray formal, informal and integrated labour markets. In these models, trading frictions in the formal and/or informal sectors are important and it is possible to determine rules governing the flows between the two sectors, as well to and from the pool of unemployed.

For most of these second generation models, the workhorse model involves incorporating the search matching model of Mortensen-Pissarides in Harris and Todaro (1970)’s model. In this case the question of how informal-formal jobs are created is not very different from the distinction between the creation/destruction of rural and urban jobs and the approach is in line with the standard equilibrium model of the labour market with market frictions and occupational/participation choice.

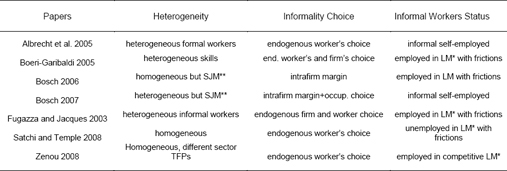

Other models emphasize the voluntary aspects of informal behavior by focusing on the worker’s decision to be in the formal or in the informal sector Albrecht et al. (2008). Similarly, a number of papers focus on the firm’s decision to open a formal or an informal vacancy. Finally, Boeri and Garibaldi (2005) and Frankel and Pissarides (2006) endogenize, both workers’ and firms’ decision to join either the formal or informal sector. Table 4 summarizes the main characteristics of this literature. Below we review in more detail the three types of models that dominate the search matching-model-based literature on informal labour markets.

Table 4.Search Matching Models: Classification

Expand

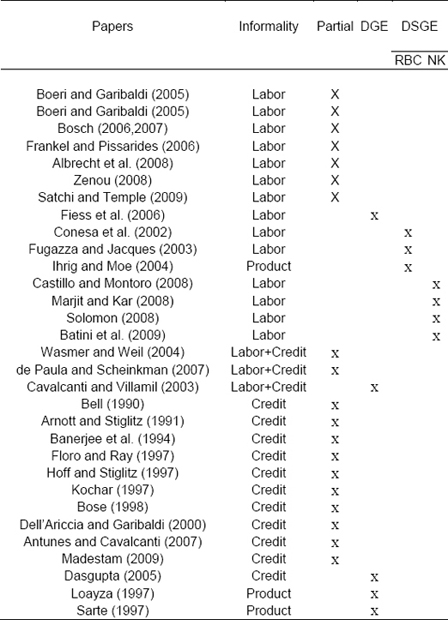

Table 5.Towards a General Equilibrium Approach to Informality

Expand

A. The Intersectoral Margin for Workers and Firms

Boeri and Garibaldi (2005) solve a deterministic search-matching model with heterogeneous workers and find that workers with different skill sort themselves between the two sectors. The intuition is the following: because informal employment (shadow employment in the paper) is associated with more labour turnover, it discourages high-skill workers. The driving assumption is that unemployment benefits are small enough, but a similar sorting can apply to a framework where the informal economy is characterized by lower capital intensity and no training commitment. The authors choose a framework with two labour markets with frictions and two matching functions. The marginal worker than is indifferent between being unemployed in the formal or in the informal sector. Also Fugazza and Jacques (2003) assume that there are important search frictions in both the formal and the informal sector since working informally requires “special connections and the access to the network is time consuming”. The model solves for two arbitrage condition, one for the firms and one for the workers. More than one equilibrium can arise depending on a parameter which summarizes the relative profitability of the regular and the irregular sectors. The analytical and numerical exercises of the paper reveal interesting policy analysis which will be discussed in the following chapters. Badaoui et al. (2006) adopt a Burdett and Mortensen search framework (Burdett and Mortensen (1998)) in which large firms pay a higher wage than small firms and concentrate in the formal sector. Small firms, instead, tend to choose the informal sector. The key factor in the informality choice is that small firms are less likely to receive a tax inspection respect to large firms. In presence of search frictions, a wage premium in the formal sector arise since large firms are more likely to pay a higher wage. The duality between formal and informal sector is explained by firm size without the need of introducing any sort of heterogeneity among workers.

B. The Intersectoral Margin for Workers

A sorting similar to Boeri and Garibaldi (2005) is described in Albrecht et al. (2008). The paper analyzes worker’s decision to enter the formal or the informal sector using a search matching model with endogenous job destruction. Workers have the same productivity in the informal sector (self-employment) while they have different productivity if they decide to enter the formal sector. In this way the relative productivity in the two sectors is an important factors in the workers’ choice. Workers with high productivity levels accept only formal job offers. There are only formal sector firms and they do not know in advance what type of worker they will meet. In this framework, workers trade-off their abilities in the formal sector with a higher job creation in the informal sector.

Also Zenou (2008) assumes that homogeneous workers in the formal sector are more productive than workers working informally. This difference in productivity is justified in terms of better technology, access to infrastructure etc. The paper shows that the informality is a result of market frictions in the formal sector.23 As Albrecht et al. (2008), Zenou (2008) distinguishes between three labour markets: the formal sector, the informal sector and ‘formal’ unemployment. In Zenou’s the informal sector is competitive and the marginal worker trade-off the higher productivity of the formal sector with the friction-less competitive market where all workers find a job. This framework largely simplifies the analysis and allows for analytical solution and interesting policy analysis. It also implies that worker’s decision to work formally or informally is based on an endogenous outside option.24

Are there more coordination failures in the formal firms than in the informal one or does the informal sector need special connections which are more time consuming? Zenou assumes at the limit that there are no frictions at all in the informal sector and this is justified by the fact that informal workers are mainly self-employed or they work for relatives and friends while formal jobs require formal application processes (see SF 10). Within the informal network, world-of-mouth communication is important and there is no need of a formal search process. This is in contrast with Fugazza and Jacques (2003). Satchi and Temple (2009) introduces a search-matching framework in a model of the Harris and Todaro (1970) tradition. The authors allow for an urban sector with formal and informal jobs and an agricultural competitive sector. As in Zenou (2008), this allows for an endogenous outside option for workers which trade-off the higher productivity of the urban sector with the security of a job in the agricultural sector. The main downside of their theoretical framework is that it does not distinguish unemployed from informal workers and the informal sectors are seen as “marginal forms of self-employment, made possible by low entry costs”. Workers that cannot find a job formally because of search frictions simply turn to the informal sector. The authors introduce endogenous capital in the formal sector of a small open economy and recognize the importance of a general equilibrium analysis. Finally, Kolm and Larsen (2003) model worker’s choice to enter the formal sector in a search-matching model where agents with different abilities have the option to acquire education. This theoretical analysis allows for the interactions and the endogenous determination of unemployment, informality and educational levels.

C. The Intrafirm Margin and the Occupational Choice

Bosch (2006) explains the rationale for the existence of both formal and informal contracts within the same firm by modeling the within firm decision of employing informal labour. Bosch (2007) generalizes the intra firm margin of informality of Bosch (2006) in a framework with occupational choice. In particular, the author assumes that heterogeneous individuals sort themselves between workers, informal self-employed and formal entrepreneurs. The latter are then able to exploit the intra-firm margins of informality by employing, both, formal and informal labour. An increase in labour market regulations can expand informality through the intra-firm contract decision and also by expanding the informal self-employment. Bosch (2006 and 2007) models the intrafirm margin by extending the basic search-matching model and allowing for ex-post match heterogeneity. Formally, the choice of a stochastic job matching framework allows for optimal hiring decision of the firm in function of the productivity of the match between firms and ex-ante homogeneous workers. Only matches with high productivity will result in formal contracts.

Comments are closed.