Below we will assume that we only take into account such political systems, which are based on democracy, where the authority comes from the public choice. Thus, theory of the public choice may be applied. We also assume that the elections are won by a political program, which proposes the greatest probability of the realization of the social needs of particular groups of society. In accordance with the concepts of the political business cycle, the rulers deliberately steer the economy in a direction that its assessment by society would maximize the number of votes. Then, economic and social policies are treated instrumentally by politicians. Politicians will tend to obtain such a state of the economy, the assessment of which by the public prior the forthcoming elections would increase the likelihood of their re-election. It does not have to be one-time behaviour; it can be repeated causing the political business cycles.

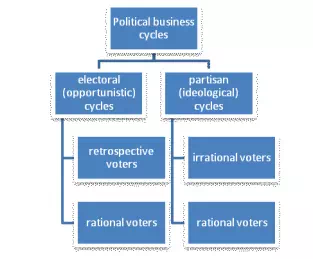

This simplistic view may, however, be more sophisticated in practice, because after the elections, some electoral campaign pledges should be fulfilled and longer-term relations with social groups supporting a candidate or a party before elections should be kept (although it may result in corruption etc.). Even though, the political business cycle may repeat. Moreover, society can identify this type of behaviour of politicians and make voting decisions keeping in mind such behaviour. Thus even when rational decisions are made, the political cycle can take place due to the fact that asymmetric information between government and society with regards to the state of the economy and scale of political decisions persists. In this case, the government’s easiest move among different macroeconomic indices is to influence spending. This will of course affect other measures of economic conditions, including inflation. If we take the short term Philips curve into account, this behaviour will have its effect on unemployment, as well, with a certain time lag (so that the unemployment rate will not rise before elections). Wherein there exists an important demarcation (although in practice it is very smooth):

• Politicians are opportunistic or ideological.

• Voters are naive or rational.

Political parties opportunistically attempt to influence voters mainly through spending money on their election campaigns and make election promises that can be so huge that later on, the society may eventually realize they are impossible to introduce. Therefore, politicians function in a populist way, hoping that they will collect more votes by fulfilling the preferences (expectations) of a majority of voters. After the elections, however, part of the promises remain unfulfilled, in hope that voters will forget them by the time the next elections come by and they will still vote for the same party. Voters can also make decisions based on their long run interests and judge the program according to its probability of coming to life (rationally). They can support an opportunistic party, if they believe the program is coherent. Ideological parties on the other hand target a certain group of voters, based on their political preferences that can be frequently expressed by either left-wing or right-wing in accordance to their political program. Again, they can treat voters as irrational or rational. Rational voters are those who fulfil the following criteria:

• Take all available information in consideration when making decisions.

• Judge the actual program and functioning of a party, and not its past behaviour.

Their expectations are rational, what means that the voters can foreshadow the effects of their own decisions and adapt to them. Irrational voters do not fulfil these criteria; they particularly consider future behaviour of a party instead of manipulative budgetary spending. If all the voters were rational, governments would not be able to influence changes in real economic indicators (such as production or unemployment). Politicians can, however, influence nominal values (inflation, transfers). Even in a highly educated population with access to information about the state of the economy and politicians, naïve voters still exist. The government is able to influence actual economic situation, and therefore the political cycle will persist both if we consider fully rational voters or only naïve ones and the mix of them.

In accordance with some research, a candidate party fighting for re-election after four years of taking the office is judged by its politics employed and introduced during these four years, and not on the basis of successes or failures of previous terms or of other previous political parties. The preferences of voters depend more on the state of the economy in the election period than what happened four years before (Mueller, 1989 p. 301). There are two major groups of effects connected with the PBC:

• The shift in the state of economy described by the change of basic macroeconomic indicators influenced by the organization of state-wide elections is called the voting or opportunistic cycle.

• The second type of political cycle appear when the economic situation is affected not by the fact of elections taking place at any given moment, but by the change of the ruling party (coalition). This can occur for even a dozen or several dozen years. This is the political or ideological cycle.

Without going into details regarding various types of business cycles, we should know that we could name several of them basing on the differences of their length. One of such probably most frequently identified cycles are the medium-run business cycles (which are also called the Juglar cycles), which last approximately 8-10 years. Another kind is the four year, short-term cycle (which we refer to as the Kitchin cycles). It is accepted that their occurrence can be caused not only by real changes, but also by the impact of politics. In the U.S., they are called the “presidential cycles”.

Comments are closed.